|

By Pieter Venter Clinging the shotline at 120m, in darkness, I anxiously peer into the black abyss for Nuno to return from a world record SCUBA attempt in excess of 315m. Statistically he has no chance of surviving unscathed and to fight my concern I remind myself that it is Nuno down there, he has a 100% chance of surviving the dive. I relax a little and wait. Finally, far below me, his helmet mounted lights flicker into view. He reaches me and behind his mask his eyes looked relaxed and happy. With a noticeable smile he showed me the world SCUBA depth record tag and I shook his hand. He just returned from a solo dive to 321.25m to meet me at 124m. He still had 12 hours before he could surface, the sea conditions are deteriorating fast, and a long hard day lay ahead. Few people can fathom what a challenge such an extreme deep dive is. More people have been on the moon than deeper than 300m. Extreme deep diving has killed or maimed most who tried and it is fraught with countless lethal and little understood dangers. Who is Nuno Gomes, why is he attempting these seemingly suicidal dives and why do I believe he can do it?  Nuno Gomes was born in Lisbon 1951. Growing up on the Portuguese coast he practically lived in the sea and learned to swim and spearfish in the temperamental Portuguese Atlantic. A clue as to Nuno’s love for diving and his seemingly obliviousness to discomfort is that when Nuno was 11 years old he would be spearing fish for hours with no wetsuit. His father who was disgruntled with the dictatorship in Portugal relocated his family to South Africa when Nuno was 14 years old. They settled in Pretoria. Landlocked. Nuno Gomes was born in Lisbon 1951. Growing up on the Portuguese coast he practically lived in the sea and learned to swim and spearfish in the temperamental Portuguese Atlantic. A clue as to Nuno’s love for diving and his seemingly obliviousness to discomfort is that when Nuno was 11 years old he would be spearing fish for hours with no wetsuit. His father who was disgruntled with the dictatorship in Portugal relocated his family to South Africa when Nuno was 14 years old. They settled in Pretoria. Landlocked.

After school Nuno got married to Liz, had two children, obtained a BSc in geological sciences, accepted a research job at WITS University and obtained an MSc in civil engineering. In 1977 he joined the WITS Underwater Club where he found like minded people who where interested in cave diving and deep diving.  In the seventies diving was not like we know it today. There were no certified instructors only mentors, no BC’s only legs, no computers or sport tables only watches and rudimentary Navy dive tables. Dives were executed with grit, fitness and determination, not the fancy equipment of today which keeps us informed, warm, balanced, comfortable and weightless. A swim to 2 Mile at Sodwana with full kit, even twin cylinders, was normal. On a WUC dive trip to Mozambique in the seventies the group lost a friend on a 1 hour swim in to SCUBA dive at Mabibi. On his fourth SCUBA dive ever, Nuno dived to 55 meters at Wondergat. The dives were challenging, exciting and most dives were into new and unexplored territory. After about 180 such dives Nuno’s mentor and instructor, Rick Bruscki, believed that Nuno was worthy, showed some promise, and he received his first diving certification, a SAUU class 3 certificate. In the seventies diving was not like we know it today. There were no certified instructors only mentors, no BC’s only legs, no computers or sport tables only watches and rudimentary Navy dive tables. Dives were executed with grit, fitness and determination, not the fancy equipment of today which keeps us informed, warm, balanced, comfortable and weightless. A swim to 2 Mile at Sodwana with full kit, even twin cylinders, was normal. On a WUC dive trip to Mozambique in the seventies the group lost a friend on a 1 hour swim in to SCUBA dive at Mabibi. On his fourth SCUBA dive ever, Nuno dived to 55 meters at Wondergat. The dives were challenging, exciting and most dives were into new and unexplored territory. After about 180 such dives Nuno’s mentor and instructor, Rick Bruscki, believed that Nuno was worthy, showed some promise, and he received his first diving certification, a SAUU class 3 certificate.

Being landlocked, cave diving was a natural progression. Nuno joined and pioneered many cave dive expeditions. He dived in all the known water filled caves in South Africa and Namibia. The early days, in 1984, saw the tragic death of fellow cave diver and caver Pieter Verhulsel in the Sterkfontein Caves. Verhulsel swimming behind Nuno in the murky water turned into a side passage and got lost. The Sterkfontein caves had many air filled chambers and Nuno believing that he is still alive started searching the area. In the meanwhile the police were notified and they stopped any civilians from further diving. The police however, found the dark murky water too scary and abandoned their efforts. Despite pleadings from Nuno and other divers they were not allowed to dive and search. Two weeks later dry cavers dug into a chamber only to find Verhulsel’s body who died only hours before they found him with a message in the sand to his loved ones.  Diving deeper and deeper just happened and Boesmansgat in the Northern Cape was perfect. In 1988 he dived to a new Africa Record of 123m. During the NAMEX 1990 expedition, the late Riaan Bouwer dropped his triple cylinder set in Lake Guinas to 120m. Nuno was the only person who could retrieve the set and he did a solo dive to retrieve the set. For Nuno, this was a big leap in the confidence needed to dive deeper than before. Dives deeper than 150m would require solo dives. In 1992 he reached 153m, alone. Diving deeper and deeper just happened and Boesmansgat in the Northern Cape was perfect. In 1988 he dived to a new Africa Record of 123m. During the NAMEX 1990 expedition, the late Riaan Bouwer dropped his triple cylinder set in Lake Guinas to 120m. Nuno was the only person who could retrieve the set and he did a solo dive to retrieve the set. For Nuno, this was a big leap in the confidence needed to dive deeper than before. Dives deeper than 150m would require solo dives. In 1992 he reached 153m, alone.

In 1993 the legendary Sheck Exley visited Boemansgat and Nuno finally met his hero. This expedition did not have a good start and on the first day of the expedition Nuno had to forego his decompression obligation to help someone from another expedition who was in serious trouble out of the water. Despite the ominous start Sheck dived to 263m, 1m short of the world record, and Nuno to his personal best of 177m. Exley, after his dive, invited Nuno to use his equipment to “go for it”. Nuno was enticed, but declined, he felt he was not ready, Exley had more than 5000 dives under his weight belt, and he did not know Exley’s equipment. He knew he would be back. Nuno learned from the legend about TRIMIX decompression schedules and calculations, staged cylinder diving, the discipline required, the seemingly obvious rule of making sure to have enough gas to breath, teamwork and to be conservative with decompression calculations. In 1993 the legendary Sheck Exley visited Boemansgat and Nuno finally met his hero. This expedition did not have a good start and on the first day of the expedition Nuno had to forego his decompression obligation to help someone from another expedition who was in serious trouble out of the water. Despite the ominous start Sheck dived to 263m, 1m short of the world record, and Nuno to his personal best of 177m. Exley, after his dive, invited Nuno to use his equipment to “go for it”. Nuno was enticed, but declined, he felt he was not ready, Exley had more than 5000 dives under his weight belt, and he did not know Exley’s equipment. He knew he would be back. Nuno learned from the legend about TRIMIX decompression schedules and calculations, staged cylinder diving, the discipline required, the seemingly obvious rule of making sure to have enough gas to breath, teamwork and to be conservative with decompression calculations.

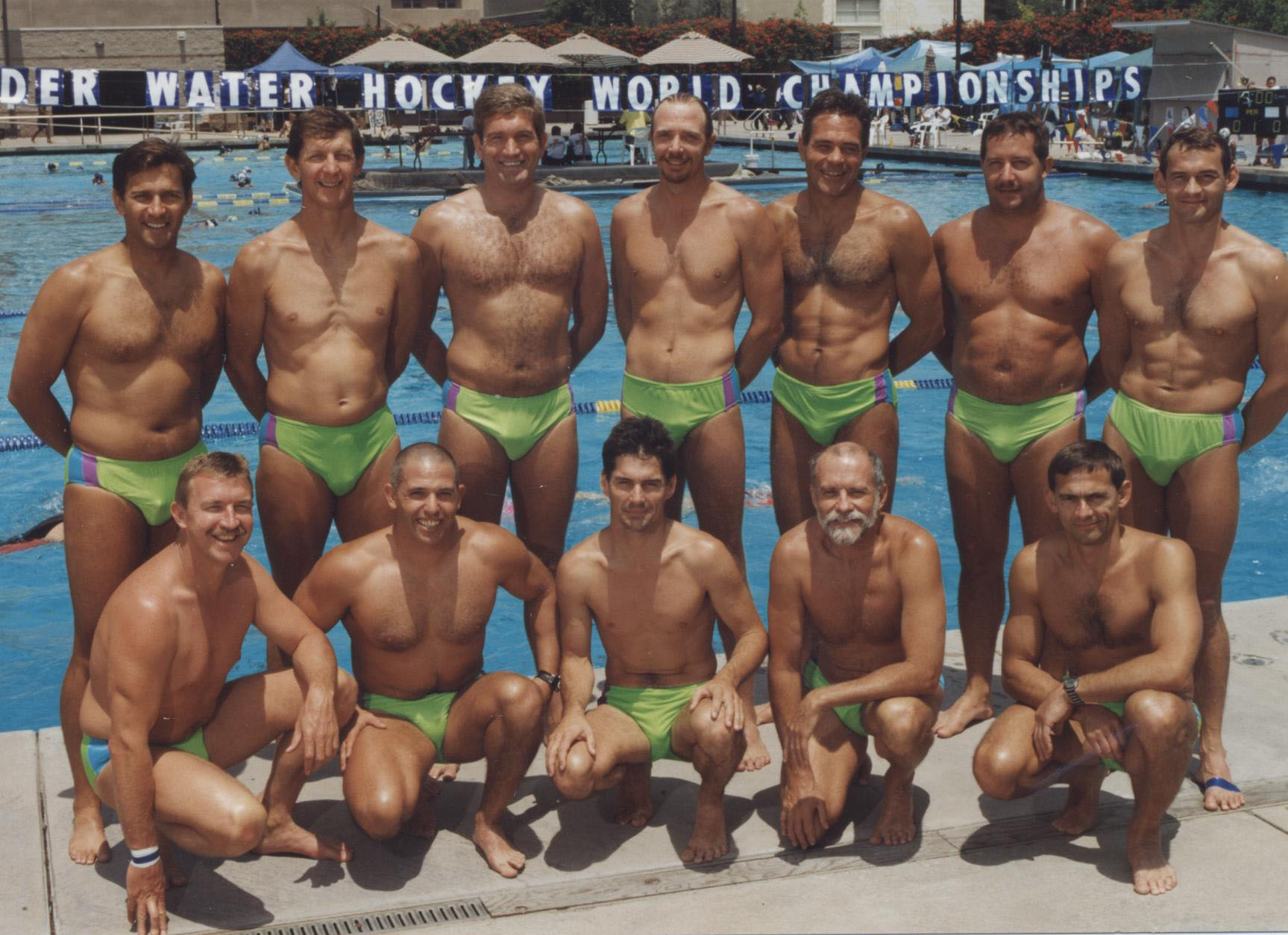

Then Deon Dreyer went missing in Boesmansgat in 1994 and Theo van Eeden, an experienced police diver, who was intent on finding Dreyer’s body contacted Nuno to help. Although Nuno declined to dive to the bottom to look for the body a fertile seed was planted and a long friendship with Theo was born.  In underwater hockey circles Nuno is already a legend. With the motto “JUST GO STRAIGHT” he sports a charge not unlike that of an Afrikaans high school rugby front row, menacing, determined, unrelenting, pummelling many a foe. Three springbok caps with two gold medals and a silver at the World Underwater Hockey Championships. Underwater hockey is a gruelling sport. Nuno still plays for the Men’s open A-league which helps to keep him fit for deep diving. In underwater hockey circles Nuno is already a legend. With the motto “JUST GO STRAIGHT” he sports a charge not unlike that of an Afrikaans high school rugby front row, menacing, determined, unrelenting, pummelling many a foe. Three springbok caps with two gold medals and a silver at the World Underwater Hockey Championships. Underwater hockey is a gruelling sport. Nuno still plays for the Men’s open A-league which helps to keep him fit for deep diving.

He also made his mark on spearfishing in South Africa. He was, at the time, and probably still, the only landlocked spearo to get Protea colours. He had no problem working at 30m and at the Navy Diving Base in Simonstown he held his breath for 5 minutes and 45 seconds and at an orientation week at WITS he breathed pure oxygen and held his breath for 11 minutes and 45 seconds.  With the bottom of Boesmansgat beckoning in the back of Nuno’s mind, he set about training for the next level of extreme deep diving. Extreme deep diving is a team effort and gradually Nuno assembled a team of dedicated divers who assisted him on his numerous expeditions to caves and sink holes in southern Africa. Key divers from WUC era include Craig Kahn, Sean French, Verna van Schaik, Lionel Brink, Joseph Emanuel to mention a few. His team consists of world-class divers and their support says a lot about Nuno’s capabilities as an extreme deep diver. They would not have supported Nuno unless they were sure that Nuno would not become another statistic. With the bottom of Boesmansgat beckoning in the back of Nuno’s mind, he set about training for the next level of extreme deep diving. Extreme deep diving is a team effort and gradually Nuno assembled a team of dedicated divers who assisted him on his numerous expeditions to caves and sink holes in southern Africa. Key divers from WUC era include Craig Kahn, Sean French, Verna van Schaik, Lionel Brink, Joseph Emanuel to mention a few. His team consists of world-class divers and their support says a lot about Nuno’s capabilities as an extreme deep diver. They would not have supported Nuno unless they were sure that Nuno would not become another statistic.

In 1994 Nuno extended his personal deepest dives to 230m followed by a 253m. During the ascent of the 253m dive Nuno experienced inner ear decompression sickness resulting from counter diffusion at the switch to air at 40m. This is a common problem for such dives and, like many other problems encountered during his long diving career, he set of to find out how to avoid this for future dives. He calls it experience.  In April 1994 the deep diving community received devastating news. Aiming to go beyond the 300m mark for the first time, legendary deep and cave diver Sheck Exley, accompanied by another leading American deep scuba diver, Jim Bowden, went down into the abyss of Mexico’s Zacaton Cave System. Exley did not resurface from 276m and Bowden, who got the bends, nearly ran out of gas and was extremely lucky to survive. Bowden was credited with an overall depth world record of 281.9 m. This news affected all divers, including Nuno. This news also had a profound effect on family members and team mates, who wondered how Nuno would survive deeper dives if the legendary Exley did not. In April 1994 the deep diving community received devastating news. Aiming to go beyond the 300m mark for the first time, legendary deep and cave diver Sheck Exley, accompanied by another leading American deep scuba diver, Jim Bowden, went down into the abyss of Mexico’s Zacaton Cave System. Exley did not resurface from 276m and Bowden, who got the bends, nearly ran out of gas and was extremely lucky to survive. Bowden was credited with an overall depth world record of 281.9 m. This news affected all divers, including Nuno. This news also had a profound effect on family members and team mates, who wondered how Nuno would survive deeper dives if the legendary Exley did not.

In the meantime, Theo persisted with his suggestions to Nuno to look for the body of Deon Dreyer and with the words “OK, it will be a world record dive” Nuno made the decision.  Nuno helped survey Boesmansgat and he realised that Exley touched down at the top of a

sloping bottom and that the cave could be much deeper than 263m. A year after his decision

to do it, Nuno and his team rigged a shotline to the deep end of Boesmansgat. In 1996

he descended to an average depth of 282.6m in Boesmansgat. “Suddenly and unexpectedly

the bottom came into sight, with only two of my torches still working (the two SabreLite

beams lit up the bottom clearly; the other two torch bodies had been squashed by the

pressure and the terminals were not making contact) my view of the bottom and moment

of glory was short and sweet. I saw a lunar type landscape of gray silt with the odd

small rock sticking out, and there was some slack rope on the flat bottom. There were

holes in the gray silt where the weights had gone in, as well as a small ledge which

I had to get past to reach the deepest spot about five meters away horizontally.

There was only one way, I had to swim whilst taking up the slack on the rope.

Since I was negatively buoyant and had no time to inflate the wings (buoyancy aids)

I landed on all fours. Nuno helped survey Boesmansgat and he realised that Exley touched down at the top of a

sloping bottom and that the cave could be much deeper than 263m. A year after his decision

to do it, Nuno and his team rigged a shotline to the deep end of Boesmansgat. In 1996

he descended to an average depth of 282.6m in Boesmansgat. “Suddenly and unexpectedly

the bottom came into sight, with only two of my torches still working (the two SabreLite

beams lit up the bottom clearly; the other two torch bodies had been squashed by the

pressure and the terminals were not making contact) my view of the bottom and moment

of glory was short and sweet. I saw a lunar type landscape of gray silt with the odd

small rock sticking out, and there was some slack rope on the flat bottom. There were

holes in the gray silt where the weights had gone in, as well as a small ledge which

I had to get past to reach the deepest spot about five meters away horizontally.

There was only one way, I had to swim whilst taking up the slack on the rope.

Since I was negatively buoyant and had no time to inflate the wings (buoyancy aids)

I landed on all fours.

My worste nightmare came true: a silt-out at the bottom of

a very deep cave with a slack guideline while on all fours and under the influence

of nitrogen narcosis and helium tremors. My first priority was to stand up without

losing balance or becoming tangled in or losing the line; the quads and two side -

mounts did not help. I tried to swim up but failed and became dizzy. I relaxed and

inflated the wings; it took 30kg of lift to ascend fifteen meters and get out of

the mud and silt." Quote extract from: THE DARKNESS BECKONS by Martyn Farr.

This dive was done at altitude with a decompression requirement of a 330m dive at sea level.

It took 12 hours to complete. On this dive Nuno wore seven cylinders (2x18, 2x14, 2x10 and one 4-litre), weighing 135 kg – using 54 730 l of mixtures of air: oxygen, nitrox and trimix. Helmet, fins, computerised gauges and pressure-resistant torches made up the rest of his gear. Nuno narrowly beat his friend Jim Bowden’s record of 281.9m and grabbed the world cave and overall depth record. The cave record was recognised by Guinness World Records and it still stands today – Guinness simply does not have a provision for a n overall dive record. My worste nightmare came true: a silt-out at the bottom of

a very deep cave with a slack guideline while on all fours and under the influence

of nitrogen narcosis and helium tremors. My first priority was to stand up without

losing balance or becoming tangled in or losing the line; the quads and two side -

mounts did not help. I tried to swim up but failed and became dizzy. I relaxed and

inflated the wings; it took 30kg of lift to ascend fifteen meters and get out of

the mud and silt." Quote extract from: THE DARKNESS BECKONS by Martyn Farr.

This dive was done at altitude with a decompression requirement of a 330m dive at sea level.

It took 12 hours to complete. On this dive Nuno wore seven cylinders (2x18, 2x14, 2x10 and one 4-litre), weighing 135 kg – using 54 730 l of mixtures of air: oxygen, nitrox and trimix. Helmet, fins, computerised gauges and pressure-resistant torches made up the rest of his gear. Nuno narrowly beat his friend Jim Bowden’s record of 281.9m and grabbed the world cave and overall depth record. The cave record was recognised by Guinness World Records and it still stands today – Guinness simply does not have a provision for a n overall dive record.

Asking Nuno typical interview questions such as “what went through your mind down there?” usually elicits a neutral non dramatic answer such as “I focus on myself and the dive plan”. Negative thoughts never cross his mind. The world of extreme deep diving is full of colourful characters. Some, motivational speaker types, come onto the scene making loud outrageous announcements of intended depth. Well sponsored, over equipped, and followed by the media they set of towards their goal. Then, usually, a few months later attempting the first real deep dive they end up in hospital never to be heard of again. Others, types, come up onto the scene after they have done an alleged world record dive with a flurry of media activities, only to have it revealed that they have no proof, that the dive went awry, that they suffered decompression illness, lost consciousness, and to be mistrusted by the deep diving community. Then there are Jim Bowden and John Bennet, who did the dive but only just made it back. Then there is Nuno. It is also a question of style.  Everybody who dived deeper than 270m suffered some form of decompression complications, in stark contrast Nuno dived deeper than 270m on three occasions, without suffering decompression complications. Everybody who dived deeper than 270m suffered some form of decompression complications, in stark contrast Nuno dived deeper than 270m on three occasions, without suffering decompression complications.

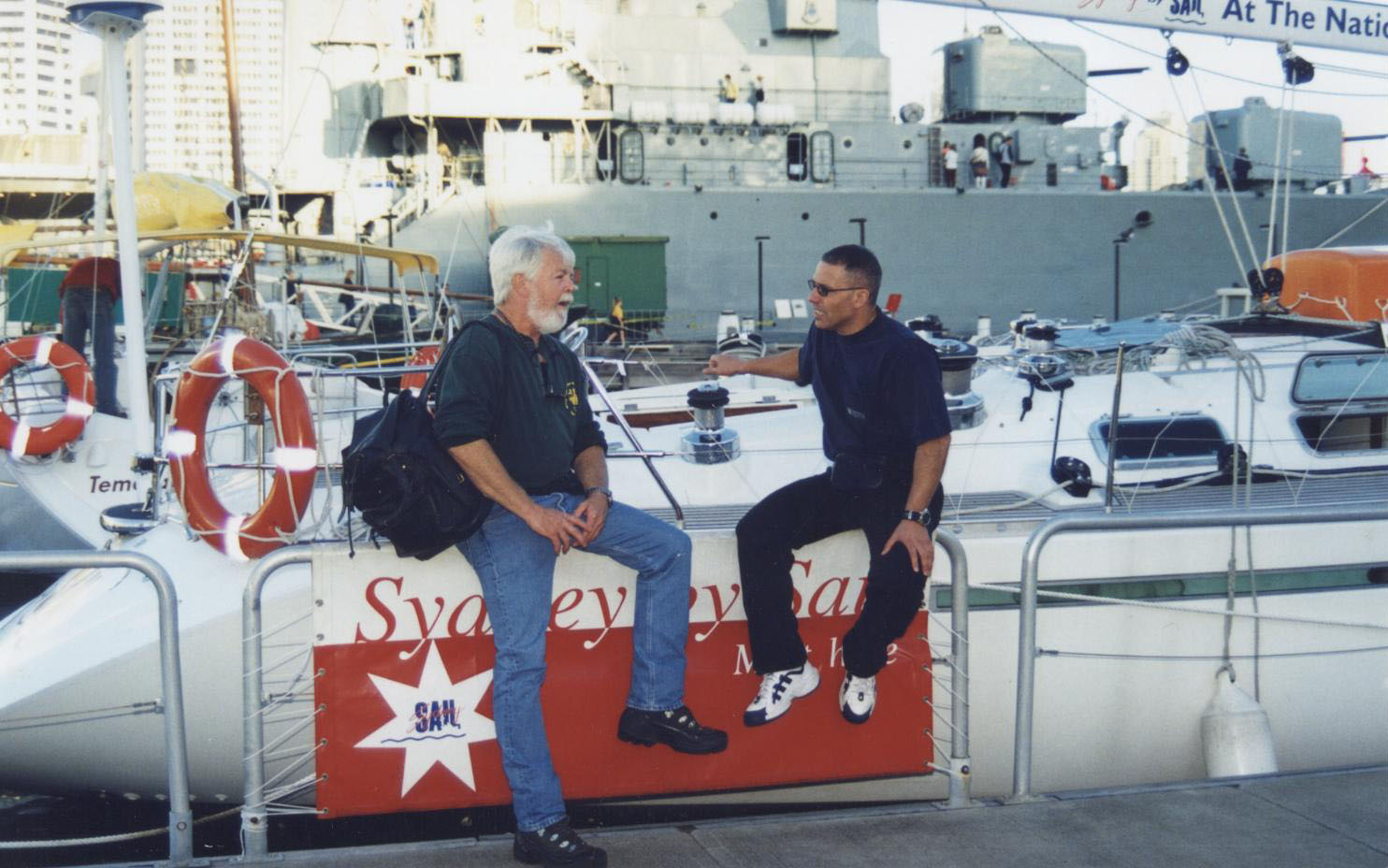

On social evenings at the WITS Underwater Club, it is easy to understand why he was supported in his quest to dive deeper and deeper. Nuno is down to earth, liked by his fellow divers and always ready to dish out his trademark smile. He respects his fellow divers and most importantly, he is their friend. For his team, it is clearly a privilege to dive with a friend and the legend.  In the same year that he got divorced, Nuno was asked to lead the dives for the coelacanth expedition in 2001 of the coast of Sodwana and to help with the planning of the dives. The dives were to be 120m deep with a fairly long bottom time of 18 minutes. The currents are usually strong with surface conditions changing during the 3 to 4 hours dive time. Nuno and the team devised a very good open water deep dive system with scheduled support divers and a free floating decompression line. Before the expedition Nuno met Lenné, who also became an important team member. While preparing for the coelacanth expedition, comfortable in the knowledge that he is the overall record holder, Nuno received the news that John Bennett descended to 307,8 m off Escarcia Point, Puerto Galera, Philippines. It was not a walk in the park for Bennett, who suffered vertigo, nausea and violent vomiting, which lasted for at least 6,5 hours. Bennett confided in an interview with Action Asia magazine (June/July 2002), that, for a few seconds, he had just wanted to let go of the guide line and go home. “But the realization that I would be dead before I reached the surface gave me something to focus on”. “White-knuckling” the guide line, he literally hung on for his life.

In the same year that he got divorced, Nuno was asked to lead the dives for the coelacanth expedition in 2001 of the coast of Sodwana and to help with the planning of the dives. The dives were to be 120m deep with a fairly long bottom time of 18 minutes. The currents are usually strong with surface conditions changing during the 3 to 4 hours dive time. Nuno and the team devised a very good open water deep dive system with scheduled support divers and a free floating decompression line. Before the expedition Nuno met Lenné, who also became an important team member. While preparing for the coelacanth expedition, comfortable in the knowledge that he is the overall record holder, Nuno received the news that John Bennett descended to 307,8 m off Escarcia Point, Puerto Galera, Philippines. It was not a walk in the park for Bennett, who suffered vertigo, nausea and violent vomiting, which lasted for at least 6,5 hours. Bennett confided in an interview with Action Asia magazine (June/July 2002), that, for a few seconds, he had just wanted to let go of the guide line and go home. “But the realization that I would be dead before I reached the surface gave me something to focus on”. “White-knuckling” the guide line, he literally hung on for his life.

With this sobering news and with the coelacanth dives going very well Nuno’s next project was confirmed, to reclaim the overall and SCUBA world record in the sea. Nuno liked the coelacanth dive system, which laid the foundations for a record dive in the sea. “The transition from caves to the sea has begun”

With this sobering news and with the coelacanth dives going very well Nuno’s next project was confirmed, to reclaim the overall and SCUBA world record in the sea. Nuno liked the coelacanth dive system, which laid the foundations for a record dive in the sea. “The transition from caves to the sea has begun”

Nuno and his team started training in earnest. Nuno stepped up his already hectic Gym program and went diving every weekend. Three expeditions were undertaken to Boesmansgat culminating in the Polish SCUBA depth and cave record of 194m by Leszek Czarnecki. During this time it was decided that the place to attempt the world record would be Dahab in the Red Sea with Planet Divers as a base. Sponsorship was obtained, flights booked, arrangements made, there was no turning back.  The team arrived in Dahab in April 2004 and started preparing for the dive. After a 150m dive Nuno declared that he was ready, only two weeks after seeing the Red Sea for the first time. He descended alone to reach past 315m. The dive did not go well. During his descent, at about 220m one of his regulators started giving problems and when he reached 271m he was forced to abort the dive switching to his bailout cylinder. The pressure squeezed the lens of his pressure gauge onto the needle locking it into the full-tank position of 200 bar, and he had no way of telling how much gas is in the bailout cylinder! The bailout cylinder was emptied just before he reached his first staged cylinder and he held his breath to get to it. This caused a chain reaction of getting just in time to the next staged cylinder and the dominoes kept falling over until his backup divers arrived. Despite the close call and the disappointment of not reaching his planned depth Nuno decided to do the full decompression schedule of 11.5 hours, for the “experience”.

The team arrived in Dahab in April 2004 and started preparing for the dive. After a 150m dive Nuno declared that he was ready, only two weeks after seeing the Red Sea for the first time. He descended alone to reach past 315m. The dive did not go well. During his descent, at about 220m one of his regulators started giving problems and when he reached 271m he was forced to abort the dive switching to his bailout cylinder. The pressure squeezed the lens of his pressure gauge onto the needle locking it into the full-tank position of 200 bar, and he had no way of telling how much gas is in the bailout cylinder! The bailout cylinder was emptied just before he reached his first staged cylinder and he held his breath to get to it. This caused a chain reaction of getting just in time to the next staged cylinder and the dominoes kept falling over until his backup divers arrived. Despite the close call and the disappointment of not reaching his planned depth Nuno decided to do the full decompression schedule of 11.5 hours, for the “experience”.

During this long decompression “experience” Nuno swallowed a lot of sea water with his fluid intake, which made him sick underwater. The team worried. Afterwards on the boat, surrounded by enquiring team members, drained but flashing his smile he remarked “This was by far my toughest dive”…”To run out of air at 280m is not a joke”…”11 hours no food no water and bobbing up and down” (his gauges read 280m as they are calibrated for fresh water)…”I am telling you I nearly didn’t make it on quite a few times, my experience pulled me through”…”however many lives you get, I used all of them” During this long decompression “experience” Nuno swallowed a lot of sea water with his fluid intake, which made him sick underwater. The team worried. Afterwards on the boat, surrounded by enquiring team members, drained but flashing his smile he remarked “This was by far my toughest dive”…”To run out of air at 280m is not a joke”…”11 hours no food no water and bobbing up and down” (his gauges read 280m as they are calibrated for fresh water)…”I am telling you I nearly didn’t make it on quite a few times, my experience pulled me through”…”however many lives you get, I used all of them”

It was a technical problem that denied Nuno the world record and he could not resist trying again. His sponsors kept their faith and provided the further backing needed to try again. It was a GO. One year later he was to Dahab, Red Sea. Nuno is not a character who can get easily upset or distracted by setbacks. It was a technical problem that denied Nuno the world record and he could not resist trying again. His sponsors kept their faith and provided the further backing needed to try again. It was a GO. One year later he was to Dahab, Red Sea. Nuno is not a character who can get easily upset or distracted by setbacks.

Everything was ready for the record dive but still we experienced a small problem: the underwater producer of “Marine Machines” John Wesley Chisolm who did the documentary about Nuno in 2004, fell sick and had to cancel his flight to Sinai. Finding an underwater videoagrapher was not a big deal, I am a very good cameraman myself, but I was supposed to fulfil another mission, I was meeting Nuno at 124 m deep. The problem was easily resolved since within the latest 3-4 months I had been in contact with Shareen Anderson and on behalf of her obsessed with deep dive records “boss” Elena Konstantinou of EKF Productions, Shareen was asking whether Nuno could give them an interview after the world record dive. They had their own underwater video crew based in Sharm el Sheikh, one hour drive from Dahab.  So we decided to pull our efforts together. To my great dismay, however, instead of one person (Valentina Cuchiara, underwater camerawoman) Shareen brought their whole international film crew to Dahab: 2 top cameramen, 1 soundman, 1 deep underwater videographer (Valentina) and her two assistants. They insisted on covering both top and underwater footage, Nuno didn’t mind, he was busy preparing for the dive of his life…” So we decided to pull our efforts together. To my great dismay, however, instead of one person (Valentina Cuchiara, underwater camerawoman) Shareen brought their whole international film crew to Dahab: 2 top cameramen, 1 soundman, 1 deep underwater videographer (Valentina) and her two assistants. They insisted on covering both top and underwater footage, Nuno didn’t mind, he was busy preparing for the dive of his life…”

Rather unceremoniously he was pushed into the water and he disappeared. He surfaced after sunset exhausted but elated. Later Nuno remarked: This time Nuno decided to use his Poseidon Cyklon 5000 regulators on both his main quad configuration cylinders as well as his side slungs. Special oil filled and glass topped Poseidon SPG’s were used on all deep regulators. A new fluid intake system was devised and the plan included 9 different gas mixtures which consisted of Oxygen, Air, 3 x nitroxes, and 4 x trimixes.  "318.25 metres/1044 feet (321.81metres/1056 feet with rope stretch) I still can not believe it!!! Well I have done it, with the assistance of my team.”  “It was not easy, no world record is, it was my second try at the sea record (also the last one) I was not prepared to have another go at it, even if I had not been successful this time around; it is just too much work not to talk about the cost.” “It was not easy, no world record is, it was my second try at the sea record (also the last one) I was not prepared to have another go at it, even if I had not been successful this time around; it is just too much work not to talk about the cost.”

“Why 318.25 metres (1044 feet)? The answer is very simple. Going any deeper would have meant my death. I would go no further, the High Pressure Nervous Syndrome (HPNS) was so bad that my whole body was going into convulsions and I barely could do the necessary to return from that depth. I was in danger of loosing the regulator out of my mouth and I was not sure I could retrieve it and place it back in my mouth”.  Nuno was destined to “return from that depth”, simply because he was supposed to face his destiny: The charming and beautiful field producer and a documentary filmmaker, - Shareen Anderson Nuno was destined to “return from that depth”, simply because he was supposed to face his destiny: The charming and beautiful field producer and a documentary filmmaker, - Shareen Anderson

“I have never been keen on scuba diving” – recalls Shareen, - “That was more of Elena’s passion. I was just there to make it work both for Nuno’s team and our film crew. Hence first time I met Nuno Gomes I fell in love madly, I couldn’t resist but think: “Gosh that was the man I have been probably waiting for… all my life”. Within almost half a year, Shareen worked hard on a postproduction of the “Beyond Blue” documentary, - “Mankind deepest dive”. They met only in January 2006, in NYC, 6 months later…  “ I cannot believe that this one small thing like missing my underwater videographer I supposed to work with during my record dive in 2005, could change my whole life. I have no words to express how happy I am, the happiest man on Earth! Now I feel like I had two dreams of life came true: I have my World Record Dive and I have the woman I love more than my record, - my Shareen”! “ I cannot believe that this one small thing like missing my underwater videographer I supposed to work with during my record dive in 2005, could change my whole life. I have no words to express how happy I am, the happiest man on Earth! Now I feel like I had two dreams of life came true: I have my World Record Dive and I have the woman I love more than my record, - my Shareen”!

“Sometimes I think like I really appreciate that my Record dive in 2004 failed. Can you imagine that if it didn’t fail, I would have never met Shareen? I can’t imagine my life without her; she is my “Baby Love”. “The Baby Love” continues to help Nuno with all his upcoming projects, she is in charge of the media events and she is dedicated to his passion deep diving as mush as she’s devoted to Nuno Gomes passion: deep diving.  In 2006 Nuno got engaged and married to Shareen, and we should see more of Nuno on television. In 2006 Nuno got engaged and married to Shareen, and we should see more of Nuno on television.

So, is Nuno a suicidal adrenaline junky? At first glance this may appear to be the case. However, with when delving deeper, it becomes clear that each dive is built on manageable incremental increases in difficulty over a very long period of time. By the time the big dive comes the envelope is pushed within his comfort zone. Each new encountered problem is solved before the next dive. He always does build-up and acclimatisation dives. He calculates decompression stops conservatively, doing long decompression time is seen as privilege not a punishment. He plans a contingency for every possible foreseeable problem. He will never be pressurised into an unmanageable dive. He knows himself. He knows his equipment. He knows his team. He is very fit. He loves diving. We can all learn from him.  PHOTO CREDITS: Nuno Gomes, Theo van Eeden, Sean French, Pieter Venter, Shareen Anderson Back |